|

R i v e r s i d e S o u t h :

I. Technology is a Tool

"Remember when we spent Christmas on the island?" I asked him. "No seriously, we had lunch on that bench around there, between the traffic lanes." I pointed. Derek was nodding, either in agreement or else just keeping time. No earbuds in his ears, because this was 1995. A car going past, Nas, Illmatic. Whose world is this? It's yours it's yours. Our plan was to meet up with Jake and Kristin in Riverside Park, down at the picnic tables at the southern tip, just by the water. I was carrying a Hi-8 video camera in my shoulder bag, a heavy and expensive item that I had signed out of the equipment room at school. When we arrived, Jake and Kristin were already there, waiting at the picnic table. It was a cold sunny day, the kind of weather that with a little wishful thinking might feel like the beginnings of Spring. The picnic was an attempt to do something different, mark the changing season, and get as far as possible from the Tisch building downtown where we spent most of our waking and sleeping hours. We were in our late 20's and early 30's but we didn't look so good, gaunt and pale from lack of sleep and bad takeout food and from all the time spent in the reflected glow of emerging media that would one day transform the world, as we knew it, of narrative, representation and shopping. Sleeping under desks, waking up beside the malfunctioning machines with which we wrestled night and day, pausing only to crash. We were grad students at a program called ITP, the Interactive Telecommunications Program at NYU, a cleverly-spun mix of entrepreneurship and media arts. It was part of the Tisch school of the Arts, and located just one floor under the NYU Film School, whose closet space and reputation we borrowed from freely. Derek wasn't in the ITP. He was an non-interactive, analogue film maker, and he had helped us with the greenscreen video on an interactive TV show called Desdemona, Queen of the Dead. This was a talk show format Jake and I had come up with in which famous and not so famous dead people were digitally revived as cartoonlike animations to be interviewed by the hostess Desdemona, played by a former porn actress. These formerly deceased persons were then ridiculed by the random and generally blotto viewers who called in while watching the show, called "Yorb," on public access cable. The system usually crashed several minutes into the show. This then was interactive multimedia. At the time, I had felt that inviting Derek in on the ground floor of this digital thing was an immense act of generosity on my part. Someday we would be sitting around smoking cigars and I would say, "Remember, Derek, when I invited you in on the ground floor of this digital thing?" and he would nod appreciatively and offer me another one of his cigars. ITP was often compared to the much more famous MIT Media Lab in glossy magazine articles, which would point out our proximity to the Film School and, by association, to the limitless pool of creativity which New York City had to offer in the way of what was then beginning to be called content. These same magazine articles would go on to describe Red Burns—the actual name of ITP's aging and autocratic director—as the grande dame or spry septuagenarian of Silicon Alley, and feature one of her pithy, enigmatic quotes: Technology is a Verb, and Technology is a Tool or It's not about Technology, etc. ITP was a two-year professional Masters program, and sometime around the end of our first year, the World Wide Web had eclipsed CD ROMs as the new paradigm, the next big thing. We were like apprentice fortunetellers, poised to tell the anxious VPs of media companies and ad agencies that what they needed was presence on this virtual frontier, which was not like anything they had ever faced before; and that this mysterious somethingorother was exactly what we would be qualified to provide. What some of us were actually beginning to understand was this: that a hustler is initiated by being taken in by other hustlers, who say "What hustle? It's just your inability to see the big picture, think outside the box." Until the marks wake up to the magnitude of the hustle that has been perpetrated upon them, and thus, the urgent need to go out and find some new game and marks of their own. In this particular variety of hustle, known as professional education, that urgent need was dictated by student loans and credit card debt: $100,000 or more of negative assets that were waiting for us once we got back to the world. This then was our education. Not all of us, to be honest, were finding our way.

II. The Picnic Jake was looking across the Hudson river at the hills of New Jersey, where the greenery was still brown, and apartment buildings were set randomly along the shore like Lego blocks. His face was animated by an array of muscular tics. He snarled as he worked his jaws around his roast beef sandwitch, neck muscles flexing against the collar of his leather jacket. He spoke out of the side of his mouth, still chewing. "So New Jersey says to Manhattan, looking out their windows, Ha, we're looking at you, and you gotta look at us. Ha!" He took a sip of his beer through a straw, which made a loud slurping noise. He poured in some more from the bottle into his large waxpaper cup. Drinking beer with a cup and a straw was something Jake did, like the ranting. "They got many fine attractions over there in Jersey," said Derek. "Lookin' at us is just one of them." Derek had the kind of wild hair and asymmetrical features that denote character actor, which is how he was usually cast —even when he himself was directing—as in such underscreened classics as The Great Cheeseman of Prague, shot on location in Central Park. "Fuck New Jersey," said Jake. "Here's an idea," said Derek, in the earnest voice he used when he wasn't serious. "For people that don't like the view out their window? You could put a big screen over it, and get a live feed from whatever view you want." "Roomwithaview dot com," I said, and started to pack a bowl. "You could link to web cams all over the world," said Kristin, without enthusiasm. She had strawcolored hair cropped very close to her skull, like a cornfield after harvest, and chiseled features that were at once cute and bad-ass. Before ITP, Kristin had been working as a documentary photographer among migrant farm workers of California, refugees in Southeast Asia and the former Yugoslavia, and other such places where the dispossessed might somehow benefit by having images taken of them. When we first met, she had just gotten the crew cut, and I wanted to run my hand across the soft stiffness of it. Now she was letting it grow in a bit. "Fuck web cams," said Jake. "Fuck corporations that give funding to shitbirds to create new kinds of art so they can put their logo on it. Virtual communities, choose your own wallpaper! Log on and pick an avatar. Feel weird? You can be the purple face! It's the brave new world wide web!" His eyes had that glassy look and were starting to roll slightly in his head. Kristin took the bottle from him and had a sip. It was that new Canadian beer, Fin du Monde. "Feel sad? Pick a blue face, click through to our pharmaceutical partners," I added, squinting, as I lit up and took a long hit. I was thinking about the project I had worked on with Kristin, an interactive version of her California farm worker photos. We stayed up for three nights designing an interface in Macromind Director, adding text and audio about the plight of migrant farm workers and the legacy of Cesar Chavez, until the only distinction between night and day was the light outside the window blinds and the choice between the lunch delivery menu or the dinner. For weeks afterwards, I'd had a sound loop from the song De Colores stuck in my head, along with a perverse craving for Welch's grape juice. "Yeah, our pharmaceutical partners. You feel like straight hair or curly hair today? We're empowering people to express themselves! Click on whatever you want, it's interactive!" The rolling of Jake's eyeballs increased, as if to take in the expanding range of possibilities. Kristin took another sip, and passed the bottle to me. I handed the pipe to Derek. "No thanks, I don't smoke pot," Derek said earnestly. "Well, OK." He took a hit. I took a swig. I passed him the bottle. He exhaled, took a swig, and handed the pipe around Jake to Kristin, who took a hit while Jake sipped loudly through his straw.

Jake was the only one who didn't smoke; he said it made him too paranoid. Once he'd described to me what it was like. "If I smoke that shit, I go straight to hell." "What," I 'd asked him, "like in Dante?" "No, it's like being trapped for eternity in a Donnie and Marie Osmond Christmas special. Everyone is wearing bellbottom jeans and they're singing. I can't get out, I have to fuck my sister, or kill somebody." The drink, on the other hand, only made him angry, which was easier for him to manage. He took steroids for a bone marrow disease (and for his weightlifting) and he took anxiety meds on account of the steroids, also painkillers for his bad hip, and these all had organized with alcohol and tobacco to form powerful syndicates. I suspected that his disdain of potsmokers might be in envy of such a benign dependence. "That shit just makes you stupid," he said to me as Kristin passed me the pipe. "I don't think so," I said quietly. I focused on the warming effect of the sunlight as it crossed the millions of miles of cold space and reached my skin and the outer layer of my clothing. "That's because it's working," he said, jabbing his index finger in my direction. "What's that over there?" said Kristin. We were at the southern edge of Riverside Park. Further down the river was a structure about five stories high, a barn of corrugated iron on two erectorset legs, with pipes coming out of its roof like chimneys. "A construction site," I said. "You know, the Trump thing. Luxury housing project." I'd heard about it in the news: Donald's Folly, Trump's Revenge, etc. A chronic city planning issue that would flare up and then go away again: could they put the highway underground, opening up the waterfront as a public space? How many thousands of new residents could the neighborhood's infrastructure handle? How high would the towers be and how long their shadow? I remembered reading once about the striped bass in the Hudson, an endangered species, how they were breeding in the old timbers under the piers that would need to be destroyed. After a few more rounds of the pipe and the bottle, we wandered down the riverbank and came to a chain link fence. A metal No Trespassing sign was attached to it, courtesy of the Riverside South Planning Corporation. Beyond the fence, we could see a huge graffiti tag—Tooney —across the side of that first structure, pitted with rust, and below it, old piers sliding into the water, an iron warehouse folding inwards on itself like the skeleton of a beached whale. "Look upon my works, ye mighty, and despair," Jake said. He poured the last of his beer to the ground, and crumpled the cup into one of the pockets of his leather jacket. He seemed almost happy. "This used to be the old railway yards." He fished through his pockets. "You got any smokes?" he asked me. "I thought you quit." "I'm just smoking cigars. No more Marlboros." "So lemme get a cigar. What kind?" "Macanudos. But I'm out."

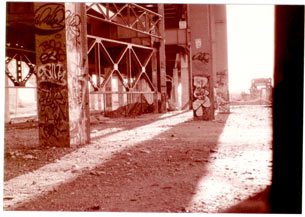

The chainlink fence extended past the water's edge. Derek grabbed the farthest post and swung around it, over the water. I followed. Jake studied the situation, cautious on account of his bad hip. Kristin noticed there was a hole in the fence, patched with wire but then opened up again, so she stepped through, holding it open for Jake. We met on the other side. "Men, this is our rally point," Derek said in a voice like Robert DiNiro or maybe John Wayne. "Anyone doesn't make it back, well, I hope it's not me." We walked through some reeds to a slight hill, a mound of dirt and cinder blocks. The vacant lot extended south all the way from 72nd down to 59th St. To our west, ruined piers and warehouses jutted into the Hudson river. Along the far eastern edge of the lot ran two tracks of the Amtrak railway line which disappeared at each end into a tunnel: one running south to Penn Station, and the other running north under Riverside Park. The highway ran four stories above us, supported by massive concrete pillars and spans of a pale green metal covered in layers of graffitti. All around was scattered a vast, haphazard construction site: bags of concrete that had hardened in the rain, cords of rusted iron for bracing the concrete that hadn't been poured. A bulldozed mountain of sand. The site was twenty blocks long and several avenues wide, nearly a hundred acres of Manhattan waterfront. It was situated well below the level of the highway and surrounding neighborhood. Unless you stood over it and looked down, you wouldn't know it was there. For all these years the old railway yards had escaped development, against all odds, and to no purpose.

"There be dragons," I said, pointing to the mouth of the northern tunnel. "Yes, the mechanical dragon," said Derek in a learn'ed British accent. "It has eyes in the front and in the back. It lives in a long, dark cave." "What does it eat?" "It eats travelers, and their luggage. Let us slay it." "I'm going to check over there," Jake said, pointing to a grafitti covered wall by some tall weeds. Derek and I began by pulling iron rebar out of the ground, to serve as our swords. We advanced toward the tunnel, but it was nearly a mile away, so we faced off against each other instead, feinting attacks and grimacing for effect. I took off my shoulder bag and put it on the ground, mindful of the video equipment inside. Derek stared me down over the tip of his drawn sword, and I stood my ground, weapon at the ready, as we circled each other slowly, unsure of what to do next. Jake had returned from the weeds, adjusting his pants under his coat. I threw my iron bar in a long arc over the field, in his general direction, trying to make it land with the point in the ground. Kristin had put away her camera, the wind blew colder. Derek lit a pipe and I passed it to Kristin. "Sometimes," I told her, "I just don't know what I'm supposed to do with myself." "How about doing whatever makes you happy, working hard at it?" "Yeah." I said, considering. I lit a cigarette. "Let me get one of those," Jake said. "I thought you quit," I said, handing him the pack. "You shouldn't," Kristin told him. We followed Jake further down the riverbank and came to a jetty. It started off solid like a boardwalk, with more planks missing as you went further out. I walked on alone, stepping carefully along a lengthwise beam until there were just the vertical posts sticking up like stepping stones above the dark rippling cold eddies. The smell was of saltwater and seaweed and decay, like a seashore somewhere else, not here. The sun was in its last agonies of sunset. Clouds of deep red draped the horizon and were mirrored on the wide slowmoving river. I made my way back to dry land. The others were huddled at the base of the jetty, where someone had assembled a sculpture garden from scrap metal: a candelabra with strange appendages; dismembered toys, dolls and engine parts; mechanical dandelions wilting in the cold wind. "Trippy," said Derek, in awe. "Who do you think made these things?" I asked. "Maybe someone lives in there." Derek pointed toward the iron tower. A sheet was flapping over the doorway at the top of a skeletal staircase. Kristin looked at the gathering darkness through her viewfinder, and snapped some pictures. "As Chaucer said in the Knight's tale," I began, "which he wrote—" "Probably just people like us, visitors." "—it is full faire a man to bear him evene, for alday meeteth men at unset stevene." "No it's the Dryads," said Jake, as if stating the obvious. He picked up a iron rod that was curved at one end, a letter J, a shepherd's staff. "Or the Druids," said Derek in a voice like Sean Connery, drawing the collar of his coat in closer around his neck. "Meaning?" said Kristin, after a pause. "Be mindful," I said, translating from Chaucer, "for we are always keeping appointments we never made." "Wood nymphs, water nymphs, other spirits," Jake said distractedly. He looked at the rod he had picked up and at the objects in the garden, as if trying to decide whether the rod were part of the arrangement. Then he rested his weight on the curve of the upsidedown J. |

|